Kerala’s Uru: The World’s Largest Handcrafted Wooden Ships and Their Ancient Origins

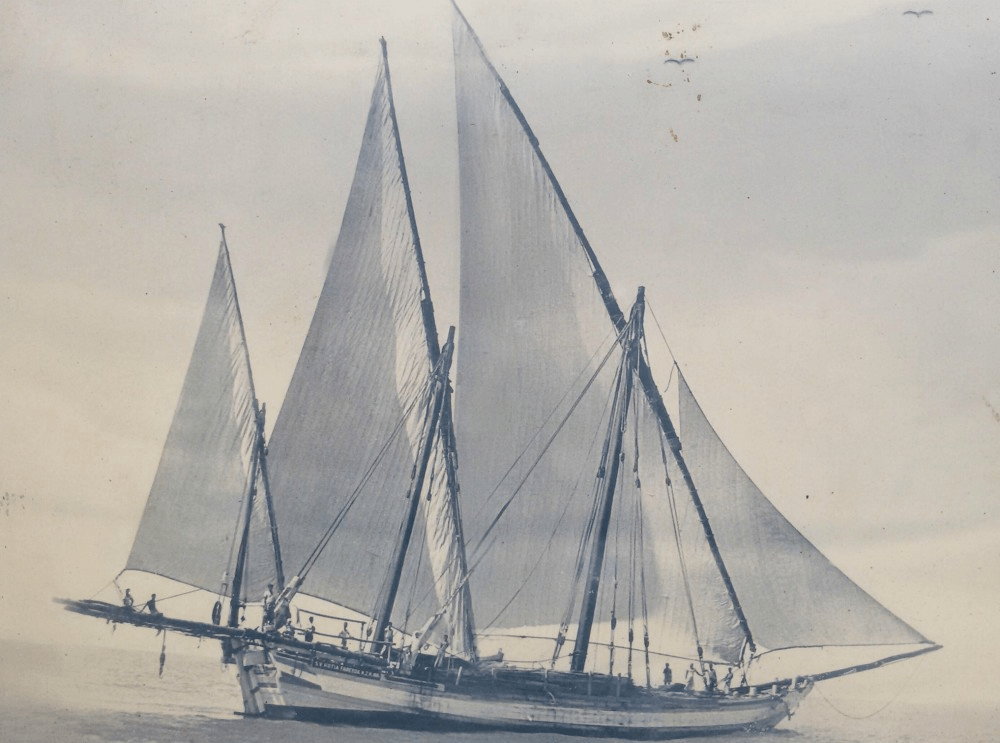

On the sun-kissed shores of northern Kerala, the air is filled with the scent of saltwater and the rhythmic sound of hammering wood. The region has been a significant trade hub for centuries, with connections to ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia and Rome. Ports here were once bustling with ships loaded with spices, ready to set sail to distant lands. Beypore, a small fishing village near Calicut, was one such port. Here, nestled by the Chaliyar River, a centuries-old tradition lives on—the making of the mighty Uru, the world’s largest handcrafted wooden ship.

2,000 Years of Tradition: The Rich History of Uru Shipbuilding

Step back in time, nearly 2,000 years, to an era when traders from distant lands first set foot on Kerala’s northern coast. They were captivated by the local carpenters’ extraordinary skill in shipbuilding. These craftsmen, known as Khalasis, could transform teak wood from the lush Nilambur forests into colossal ships capable of sailing across the seas. These vessels, known as Urus or ‘Fat Boats,’ were not just ships; they were lifelines, ferrying goods, people, and stories between India and the Middle East. In those days, owning a Uru was considered a status symbol among Middle Eastern traders, with the larger and more ornate vessels reserved for the wealthiest merchants and royalty.

Unique Types of Urus: From Pathemar to Sambook

Each Uru was a masterpiece, handcrafted to serve a specific purpose. Whether it was the sturdy Pathemar for transporting goods, the majestic Sambook used by Arabian traders since the 11th century, or the intricately carved Bahla reserved for royalty, these ships were as varied as the oceans they sailed. There was the Mangalore Padavu, with a width larger than its length, and the Thoothukudi, affectionately known as the cock’s nest, each vessel carrying with it a unique identity and purpose. Some Urus were so luxurious that they were considered floating palaces, adorned with ornate carvings and lavish interiors, making them more than just a means of transport.

Types of Urus

• Kottiya: Width is one-third of its length.

• Pathemar: Goods ship.

• Sambook: Used by Arabs since the 11th century A.D., with a width less than half its length.

• Donki: Small ship.

• Batala: Used mainly on Karwar coasts.

• Thoothukudi: Also known as Kozhikazhuthu (cock’s nest).

• Mangalore Padavu: Width larger than its length.

• Padavu: Also known as Padagu.

• Boom: Huge cargo vessel.

• Bireek: Royal looking.

• Bahla: Finished with elaborate carvings and beautiful arches.

• Dhoni: Also known as Thoni.

• Manchi: Another variety of Uru.

A Journey from Teak to Masterpiece

The creation of a Uru is nothing short of magical. There are no blueprints or sketches; instead, the entire design lives in the mind of the master carpenter, the ‘Maistry.’ With a team of over 40 skilled artisans, he breathes life into the wood, assigning each task with precision, ensuring that the ancient secrets of Uru making remain closely guarded. The knowledge of building these grand vessels is passed down orally, with only a handful of master carpenters fully understanding the intricate process.

The process begins with the keel, the ship’s backbone, laid with care and reverence. Slowly, layer by layer, the Uru takes shape. The artisans, using simple tools and age-old techniques, work tirelessly, often taking up to four years to complete a single ship. During the construction, the Khalasis sing traditional Mappila songs, which not only entertain but also help synchronize their movements, especially when launching the ship into the water—a process that itself is a community celebration akin to a festival.

The Survival of Uru Making in the Modern Era

Despite its grandeur, the tradition of Uru making faced a decline. By the 1970s, the demand for these wooden marvels dwindled. The rise of metal ships, the scarcity of teak wood, and the changing tides of global trade nearly wiped out this ancient craft. Many artisans left Beypore, seeking work in the Middle East, their skills slowly fading into obscurity.

But just as the sun sets, only to rise again, the craft of Uru making found a new dawn. In 2011, the royal family of Qatar commissioned a luxury cruise ship, sparking a revival in Beypore. This order not only saved the craft but also brought international attention to the Uru. Once again, the Khalasis took up their tools, their hands steady with the knowledge passed down through generations. Since then, orders from the Middle East for luxury yachts and traditional vessels have breathed life into this fading tradition.

Why the Uru Is More Than Just a Ship: A Cultural Icon of Kerala

Today, a Uru is more than just a ship; it’s a symbol of cultural heritage, a living testament to the ingenuity and artistry of Kerala’s craftsmen. These vessels, with their timeless design and unmatched durability, stand as a reminder of a glorious past and a beacon of hope for the future. The legacy of Uru making is not just in the ships themselves but also in the secrets and stories embedded in every wood plank.

As you walk along the shores of Beypore, watching a Uru being crafted, you can’t help but feel a connection to the past—a past where the world was bound by the wooden planks of these magnificent ships. The Uru is not just the largest handicraft in the world; it’s a story of resilience, tradition, and the enduring spirit of a small town in Kerala that continues to build dreams on the water.

Check out some of the tours that feature the Uru on HimalayAsia:

-

Explore South India (14 Nights /15 Days)

2500,00 €